In 2022, I looked closely at Practical Law’s template of a mutual confidentiality agreement. I thought it appropriate to now finalize that analysis and make it available to anyone inclined to read it. Go here for a PDF in which I highlight the issues I spotted and offer a brief take on each.

Background

Practical Law is part of Thomson Reuters. According to TR, “Practical Law is driven by 300+ seasoned attorney-editors whose sole job is to create and maintain timely, reliable, and accurate resources across all major practice areas.” TR acquired Practical Law in 2013. I assume that in the United States, its clients include all the biggest law firms. Among its offerings are contract templates.

Which Template?

Because I wasn’t about to devote a whole lot of time to this exercise, I looked at just one template. It had to be something basic and widely used, and it had to be for a kind of transaction I was comfortable with, so I went with their mutual confidentiality agreement. Or more specifically, “Confidentiality Agreement: General (Mutual).” It wasn’t an exciting choice, but it made the task manageable. I started my review in 2022 (hence the 2022 date in the introductory clause in the annotated PDF), then I set it aside for a year. When I resumed my review, I checked whether Practical Law had made any changes to their template—they hadn’t. I revised my comments and updated all references to A Manual of Style for Contract Drafting so they cite the fifth edition.

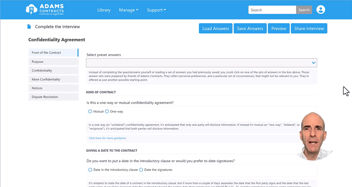

Like Practical Law’s templates generally, this template offers some customization—you’re presented with a short questionnaire powered by Contract Express, the document-assembly software that TR acquired. (I used Contract Express before TR acquired it.) In addition to questions asking you to provide information about the parties, give a date for the contract, state the purpose of the contract, and choose the governing law, seven yes-no questions invite you to adjust the contract in other ways. To create my version of their confidentiality agreement, I answered “Yes” to all those questions.

Is it fair for me to draw conclusions about Practical Law’s templates from looking closely at just one template? I think so—it’s reasonable to expect that their contract templates are of consistent quality. I looked at a couple of other templates (a professional services agreement and a distribution agreement), and the drafting looked broadly comparable to that of the confidentiality agreement. The boilerplate differed in the details, suggesting that their approach isn’t strictly modular. Unlike the other two templates, the confidentiality agreement template was described as being by Practical Law and a named law firm partner, as opposed to being just by Practical Law.

From "Bad" to "Worse"

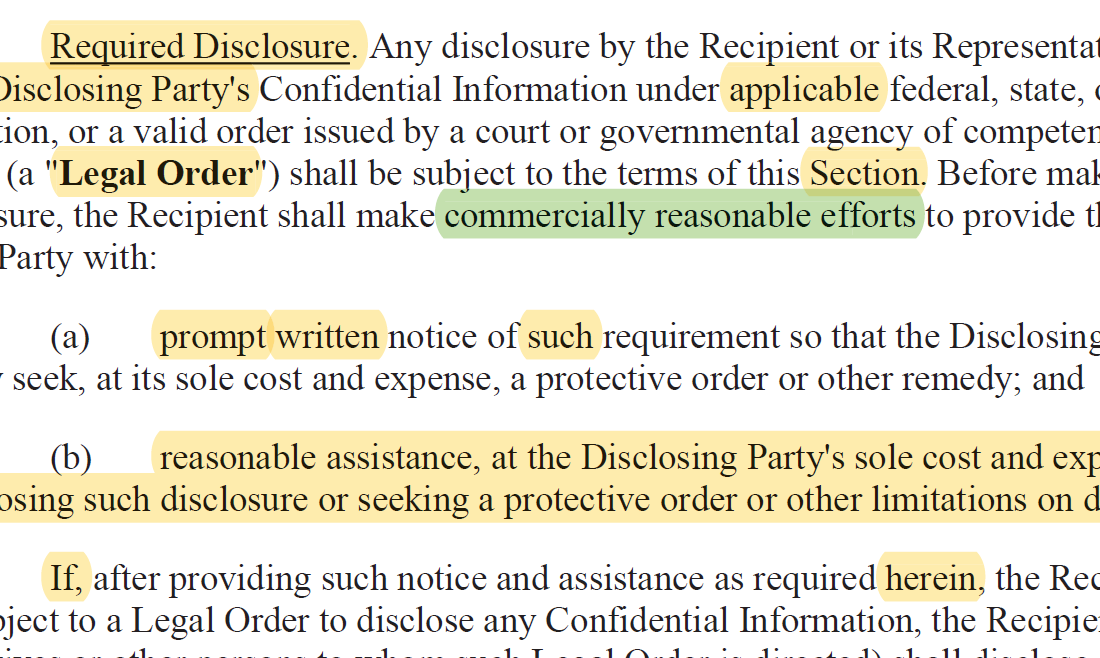

I used a deeply unscientific color scheme for my annotations—yellow for drafting that’s bad, green for drafting that’s worse.

To be rated “bad,” drafting need not create a serious problem. Instead, it’s enough that it be archaic. Or wordy. Or redundant. Or awkward. That kind of drafting results in contracts that are less clear and less concise than they should be. The reader wastes time and has to work harder.

Included among the “bad” drafting are two document-assembly glitches that suggest that TR hasn’t taken full advantage of Contract Express’s functionality.

I rated “worse” anything that’s particularly wasteful, that’s confusing, or that’s an unhelpful way to express a deal point.

The Upshot

What do these shortcomings signify? That’s for you all to decide. If you’re satisfied with traditional contract drafting, you likely won’t notice anything amiss with this Practical Law template. But if you’re looking for quality, the nature and extent of these shortcomings should give you pause for thought.

The “bad” (as opposed to “worse”) drafting by itself is enough to undercut the drafter’s credibility. It signals to informed consumers of contract language that the drafter is cranking the handle of the copy-and-paste machine, either because they don’t care or because they don’t know any better. If a drafter isn’t discerning in how they handle the small stuff, that’s reason enough not to trust them regarding the bigger stuff.

What explains these shortcomings? They can be attributed to the systemic dysfunction in contracts, which is the result of mass copy-and-pasting, aggravated by the legalistic mindset. I’ve seen the same dysfunction in organization after organization—it’s the norm. I would have been surprised if Practical Law had escaped it.

Why Offer This Critique?

I’ve long done this kind of analysis. (See what Casey Flaherty says about that in this 2018 blog post.) I do so to highlight the dysfunction in mainstream contract language, which takes a tremendous toll. By making contract language harder to read and more confusing, it wastes time and money at every stage of the process: drafting, review, negotiating, and monitoring enforcement. It can result in suboptimal outcomes in deals that get done. It can result in deals getting so bogged down that they don’t get done. It can hurt your competitiveness, if your competitors have clearer contracts. It leads to disruptive disputes, with some ending up in messy and expensive court or arbitration proceedings. And it demoralizes those who work with contracts.

So if this analysis sensitizes anyone to contract dysfunction and shows them the benefits of a more disciplined approach to contract language, so much the better.

But for anyone paying attention, it has long been clear that mainstream contract language is dysfunctional—continuing to harp on that would offer diminishing returns. It’s also clear that fixing the copy-and-paste system poses a challenge that goes way beyond identifying suboptimal drafting. That’s why in this post from earlier this year I said I was no longer inclined to critique how organizations draft their own contracts. (And that's why I started Adams Contracts.)

But it’s still appropriate to scrutinize those who presume to tell us how to draft contracts and those who sell contract templates.