Notorious troublemaker Glenn West thought I might find of interest a draft article on SSRN (here). It’s by Jorge L. Contreras, and the title is “Solving for Agreement.” It’s about attempts over the years to automate contract drafting.

Although it’s unpublished, I did indeed find this article interesting. It allowed me to consider the strengths and weaknesses of using document assembly for contract drafting and how it compares to using artificial intelligence for contract drafting.

How Document Assembly Works

Here’s how Contreras describes document assembly:

The document assembly software discussed in Section I.C worked by knitting together blocks of contractual text into an agreement, guided by user responses to conditional logic questionnaires (e.g., What is the price of the contracted goods? Should the confidentiality obligation be mutual or one-sided? Should disputes be resolved by arbitration or litigation?) Their goal was to produce a customized, integrated contract that reflected the specific “deal points” agreed by the parties.

That’s a decent summary of how document assembly works. But in his article, I think Contreras both overestimates and underestimates document assembly.

Document Assembly Isn’t a Success

He overestimates document assembly by referring to its “success in the marketplace.” Apparently, that’s based on a 2021 survey in which 36% of respondents reported using document assembly software in their legal practices.

But my sense, based on my conversations with people involved in document assembly and my experience in selling document-assembly products, is that document assembly has chronically underperformed. Here’s what Catherine Bamford, one of the leading figures in document assembly, said in a LegalGeek talk in 2023 (here):

Document Automation is STILL not widely used. It is not the business as usual way the majority of lawyers prepare legal documents. Most lawyers still find a precedent and manually edit it in Word.

Document Assembly Allows for Complexity

But Contreras also underestimates document assembly by saying this:

While such systems are useful for routine and high-volume transactions such as residential leases, employment agreements and nondisclosure agreements, they generally lack the capability to produce more complex agreements for business transactions.

Nothing about document assembly limits its use to simpler transactions. Instead, it allows you to implement any customization you might need, whether simple or complex. I expect that some proportion of document-assembly users have created sophisticated templates for their own use, but we don’t get to see them.

Instead, we get to see, for example, Practical Law templates, which incorporate document assembly, using Contract Express. My analysis of Practical Law’s mutual-confidentiality-agreement template (here) says this:

In addition to questions asking you to provide information about the parties, give a date for the contract, state the purpose of the contract, and choose the governing law, seven yes-no questions invite you to adjust the contract in other ways.

Limiting your customization to seven yes-no questions, with blocks of text being included or omitted, is setting the bar very low.

At the other end of the spectrum you have Adams Contracts’ confidentiality agreement template. I haven’t gotten around to counting the questions—let’s just say there are more than one hundred (although any user would be invited to answer fewer questions than that). Furthermore, some parts of the decision tree for that template contain several branches, so one question could lead to other questions, which could lead to yet further questions.

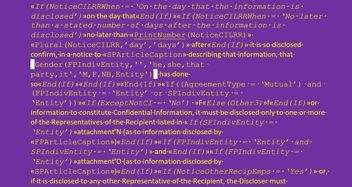

And any given customization might cause multiple changes throughout the document. For example, in my earlier confidentiality agreement template—built a dozen years ago using Contract Express—changing the contract from one-way to mutual caused more than 700 changes in the underlying Word document. Making that change in the Adams Contracts template likely causes an even greater number of changes.

So Contreras is mistaken in saying that document assembly is incapable of producing complex contracts. Instead, document assembly allows the user to quickly create contracts that are simple or complex, as the user requires.

Why Document Assembly Has Languished

Despite the flexibility of document assembly, it has languished, for several reasons. The work involved in compiling and then automating the contract language is demanding. Then you have the question of whether you can achieve economies of scale to justify investing in document assembly. And you also have to overcome the black-hole level of inertia that has the world of contracts in a stranglehold. I explore these factors in this 2023 blog post.

That explains why only Adams Contracts is attempting to build highly customizable templates for use by anyone willing to pay a modest fee.

The Problems with Artificial Intelligence

At the same time, Contreras see limited potential for using AI to draft contracts:

The results of [a recent] study, as well as our interviews and reviews of the literature, suggest that while advanced GPT-based LLMs can assist transactional attorneys with contract drafting tasks, particularly by locating relevant clauses from a firm’s or company’s contract files, even these sophisticated tools are not yet capable of drafting a complete agreement for a complex transaction absent an existing document template.

Contreras offers as reasons a lack of training data, AI’s inability to anticipate eventualities, AI’s tendency to invent (“hallucinate”), AI’s inability to create reproducible results, the potential for hidden bias, and lack of transparency.

To Contreras’s list I would offer a more basic failing of AI—because mainstream contract drafting is dysfunctional, it’s inevitable that AI trained on that dysfunction will replicate it.

Why the Proposed Fix Won’t Work

Here’s what Contreras sees as a potential fix:

Specifically, contract-generating GenAI tools should be pre-loaded with a set of industry-adopted consensus templates that serve as the basis for AI-generated contracts of the relevant types (e.g., a consensus template for construction contracts would serve as the basis for construction contracts generated by the tool).

One problem with Contreras’s solution is that consensus templates aren’t free of the dysfunction that pervades mainstream contract drafting. For example, the American Institute of Architects templates, which Contreras mentions, are notoriously clunky. That’s why a few years ago a big company was sufficiently frustrated to hire me to explore the possibility of creating an alternative to the AIA documents. Feeding the AIA templates to AI wouldn’t seem much of a solution.

But the problem with Contreras’s proposed solution goes beyond that. All the consensus templates Contreras mentions are static templates. As such, they’re inherently limited.

The most valuable component of any drafting system is customization. That’s what document assembly offers, if those who are at the controls are up to the task. AI can only offer erratic, uncontrolled customization. Add to that its other shortcomings, and can't see AI as an effective vehicle for quality contract drafting.