Like the title says, the consequences of bad contract drafting are uncertain, or they aren’t immediate. That complicates the task of fixing contracts.

Let’s consider first the sources of contract-drafting dysfunction:

- Contracts are hard, because understanding deal mechanics is hard. Because keeping abreast of the law is hard. Because saying clearly and concisely whatever you want to say in contracts is hard.

- Because contracts are hard, it’s not realistic to expect those who work with contracts to decide, from scratch, what to say in each contract and how to say it. Instead, because any given transaction likely resembles other transactions done previously, our best option has been to base contracts for new transactions on contracts done for previous transactions.

- But thanks to generations of copy-and-pasting, we’re copying words that other people copied from other people who copied, and on and on. Our understanding of what we’re copying isn’t just secondhand, or thirdhand, it’s nthhand, so routinely there’s a disconnect between what we’re saying and what we think we’re saying. And much of what we’re copying is immune to understanding—it doesn’t make sense.

- And when you copy from contracts used for other transactions, it’s easy to copy elements that don’t reflect the new transaction, and it’s hard to crawl back up branches of the decision tree that were ignored in the contracts you copied from.

- Although copy-and-pasting is more efficient than drafting from scratch, it’s also less efficient than other ways of handling the drafting process.

All that could be managed, except that contracts aren’t like software code, where bugs tend to be rooted out relatively quickly—otherwise, it would be apparent to the user that the software doesn’t work as advertised, or doesn’t work at all.

Instead, the consequences of bad contract drafting aren’t immediate, or they’re uncertain. It’s easy to ignore the drip-drip-drip of time and money being chronically wasted. It’s easy to dismiss the risk of getting involved in an expensive, disruptive, and potentially embarrassing dispute. And the benefits of fixing contract language aren’t easy to quantify.

Those costs and benefits matter only if you plan for the long term. If you’re focused on the short term, they’re easy to ignore.

Furthermore, because the consequences of bad contract drafting aren’t immediate or aren’t certain, that permits various narratives that compete with the most obvious course of action, which is to address the dysfunction directly. Here are the narratives that come to mind:

- You defend the dysfunction, because you can’t accept that a function as vital as contracts, and a profession as distinguished as the law, should be built on such a shaky foundation. (I encounter this occasionally from the old-guard legal establishment.)

- You ignore the dysfunction. You’re not committed to actual quality, because that’s too hard. Instead, you’re satisfied with the appearance of quality. Slap a “contracting center of excellence” sticker on it and you’re done. (See this 2021 blog post.) A limited interest in quality might explain why no organization has ever contacted me regarding my critique of one of their contracts—even those I’ve reached out to before publishing my critique.

- You’re aware of the dysfunction, but you underestimate what it takes to remediate it. Just draft more clearly! So high-school students can understand your contracts! (See this 2017 blog post.)

- You’re aware of the dysfunction, but your interest in fixing it is limited to contributing to the endless round of chatter on social media. (See this 2022 blog post.)

- And periodically, the legal profession will, to no avail, look to others to save the legal profession from itself. After knowledge management, blockchain, and other buzz phrases, we now have generative artificial intelligence. (See today’s other blog post, here.)

I’ve long thought that the only fix for what ails contract drafting would be for someone to build a library of highly customizable automated templates. That’s what I’ve started doing with Adams Contracts. It promises to be a straightforward, unglamorous, and effective solution, but it competes with those other narratives.

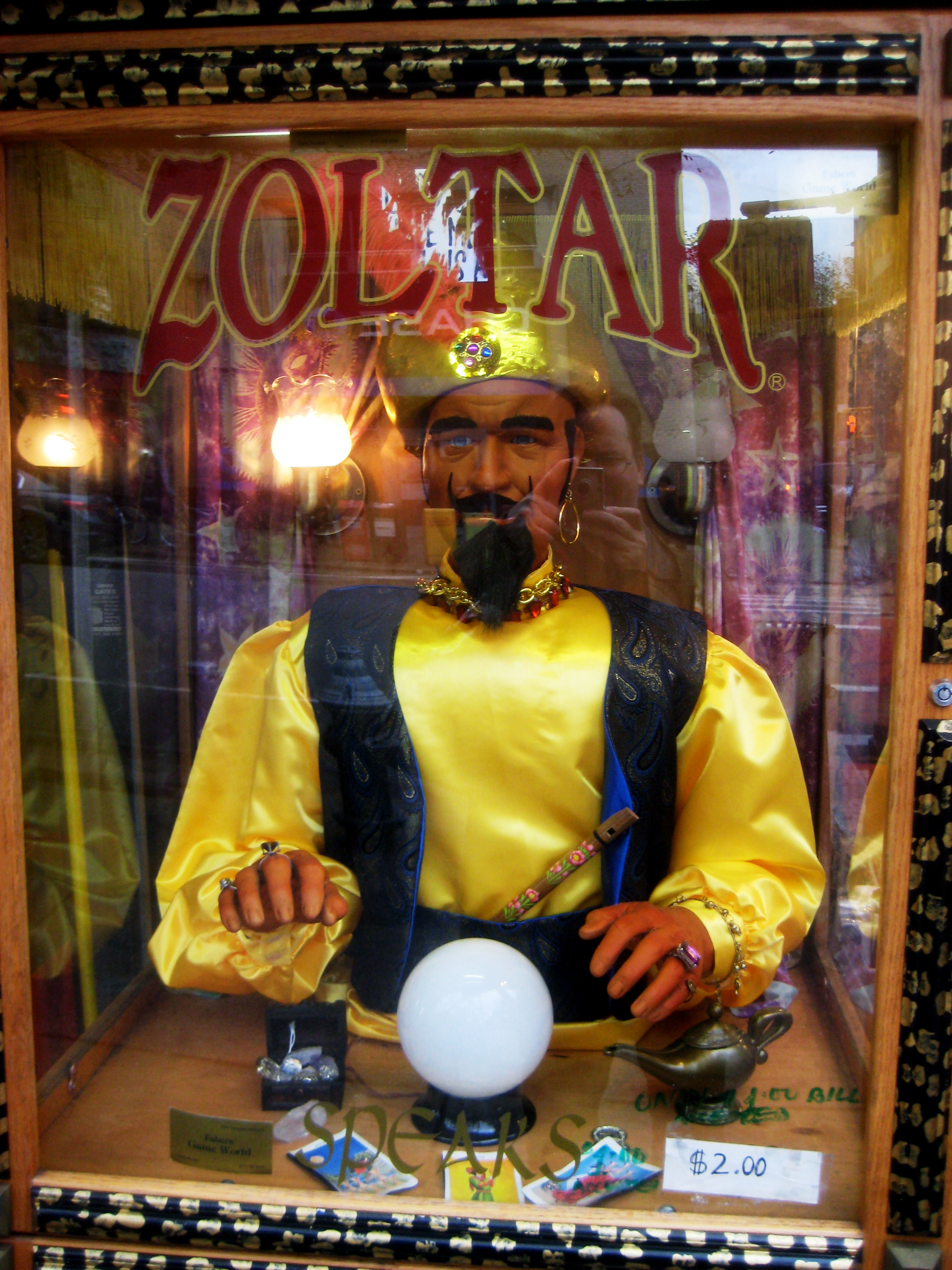

(The image above is by Brecht Bug. It's available on Flicker; I'm using it under a Creative Commons license.